As a talent professional, you have undoubtedly heard a lot of talk about skills over the last few years — upskilling, reskilling, skills sets, skills gaps, skills assessments, and skills-based hiring — to the point you have a skull full of skills.

And you’ve probably come to see that a skills-approach to talent acquisition and talent development requires a lot of work.

But as you’ve considered where skills might best fit into your organization’s approach to talent management, have you also thought about your own skills, about developing them and — just as importantly — showcasing them?

More pointedly, have you thought about whether your own LinkedIn profile accurately captures your skills?

Why it’s important to list your skills on your LinkedIn profile

Increasingly, skills — as much as schooling, previous companies, job titles, and work experience — are what get you a new job.

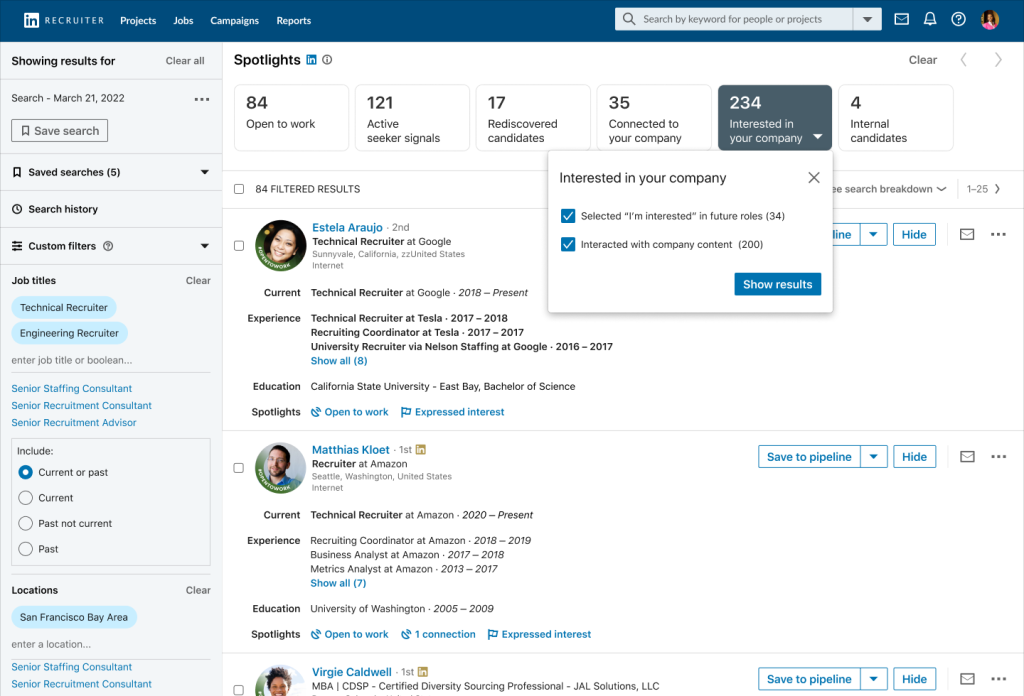

As a talent pro, you know that AI-powered tools used by recruiters to screen candidates will look to see how well a professional’s list of skills matches what’s needed for an open role. In addition, recruiters themselves will infer skills by looking at a candidate’s job experience, schooling, and activities, by asking the right questions in an interview, and by talking to references. Nearly half (48%) of hirers on LinkedIn now explicitly use skills data to fill their roles.

You make their job easier by listing your skills and accurately stack-ranking them.

According to LinkedIn data, members who list at least one skill, receive up to 2x more profile views and connection requests and up to 4x more messages.

And as a talent professional, you need to model the importance of highlighting skills on your LinkedIn profile:

- If you’re a recruiter, having your own skills up to date gives you a platform from which to coach candidates who have loads of talent but aren’t showcasing it on their resume or profile.

- If you’re a learning and development (L&D) professional, being current with your own skills gives you a chance to model for your colleagues how critical this is for charting their professional growth and career development.

Which skills — and how many — you should list

LinkedIn allows you to post up to 50 skills on your profile, enough that anyone will be able to see how talented and indispensable you are. You’ll be choosing from over 41,000 skill titles, so you do want to be thoughtful and selective. At the same time, you’ll want to be somehow comprehensive. So, make the most of your 50 opportunities.

Given that sea of opportunity — 41K choices — how should you focus? Start by thinking about what your next dream job would be: Director of technical recruiting? Talent development manager? Digital learning designer?

And then hop on LinkedIn and see what skills are listed in postings for your dream job. If you’re a recruiter who’s recruited other recruiters, think about what you’ve asked for when you’ve written job posts. What did you want to see from job seekers?

Make sure you list the skills that you’ve mastered and that pop up like clockwork in job descriptions. Consider leveraging LinkedIn Learning or other professional development opportunities to acquire any critical ones that you’re missing.

As you weigh which skills to list and which skills to develop, consider the skills that most frequently appear on LinkedIn profiles.

Top Overall Skills on LinkedIn

- Communication

- Teamwork

- Problem-solving

- Analytical skills

- Leadership

- Sales

- Management

- Data analysis

- Team leadership

- Organizational skills

Top Soft Skills on LinkedIn

- Communication

- Teamwork

- Problem-solving

- Analytical skills

- Leadership

- Management

- Team leadership

- Organizational skills

- Interpersonal skills

- Negotiation

Top Hard Skills on LInkedIn

- Sales

- Data analysis

- Marketing

- Customer relationship management (CRM)

- Python (programming language)

- Research skills

- SQL

- Business development

- Training

- Social media

Of course, the frequency with which these skills show up isn’t a perfect predictor of what recruiters and hiring managers are looking for. Neither is it an ideal guide to what learning leaders are trying to teach and develop.

Every year, LinkedIn announces the most in-demand skills after looking at which skills turn up most frequently in job postings and the profiles of members who have either been hired recently or contacted by a recruiter.

Most In-Demand Skills

- Communication

- Customer service

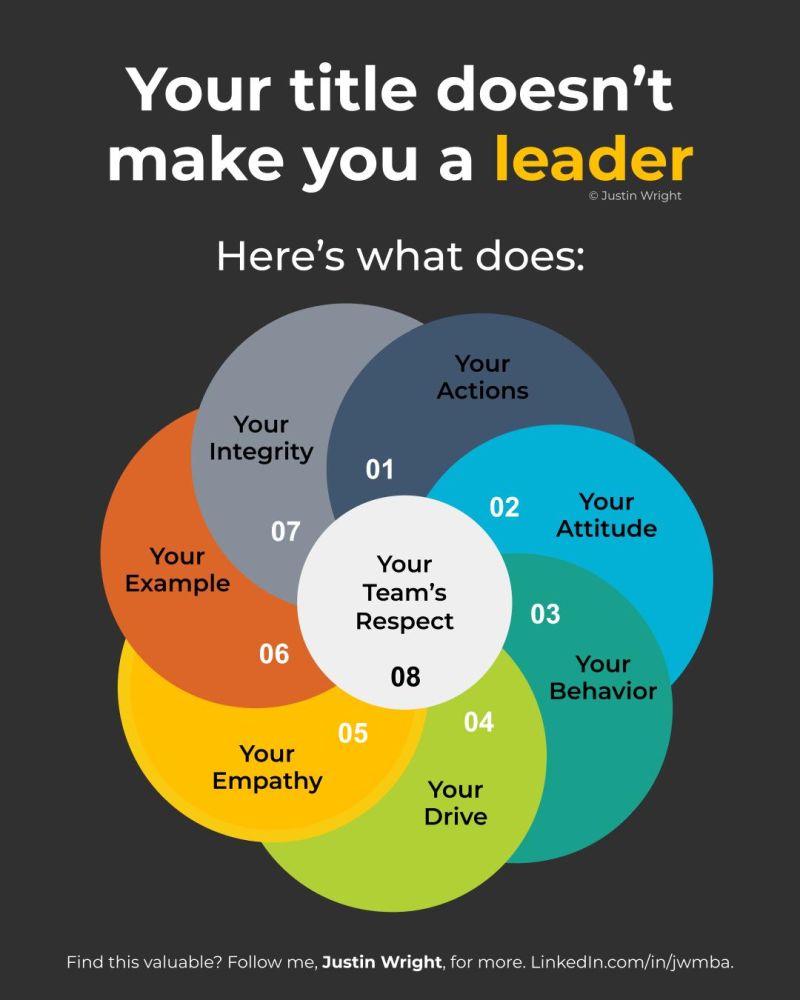

- Leadership

- Project management

- Management

- Analytics

- Teamwork

- Sales

- Problem-solving

- Research

LinkedIn has also produced a list of the most in-demand skills for recruiters and for L&D professionals.

Be as specific with your skills as possible

God, as they say, is in the details. Where appropriate, list specific skills rather than generic skills or umbrella terms.

For example, you may have noted that communication is the most frequently listed skill on LinkedIn members’ profiles. To differentiate yourself, it will help to call out the specific skills you have that fall under that broad umbrella:

- Speechwriting

- Executive comms

- Internal comms

- Blog writing

- Copywriting

- Visual communication

Perhaps you’re a recruiter, so your list of skills includes sourcing. But are there specific roles you’ve recruited for that require specialized knowledge and tactics? So, if you’ve been a recruiter in the tech sector, call that skill out. Better yet, if you were hiring software engineers from Southeast Asia or Eastern Europe, include that too.

List the hard skills that define you and what you can do

Hard skills are the technical skills you develop through hands-on experience, training, or education. They often involve using a machine, software, or tool. They range from Microsoft Excel and data analysis to SQL and digital marketing to sourcing and curriculum development. And they are usually top of mind when someone talks about skills gaps or skills-based hiring.

You want to include the hard skills that are your strengths and that are what companies are looking for. These will give you credibility with recruiters, hiring managers, and even colleagues. Where possible, bolster your profile by pointing to training, education, and certifications that support your claims.

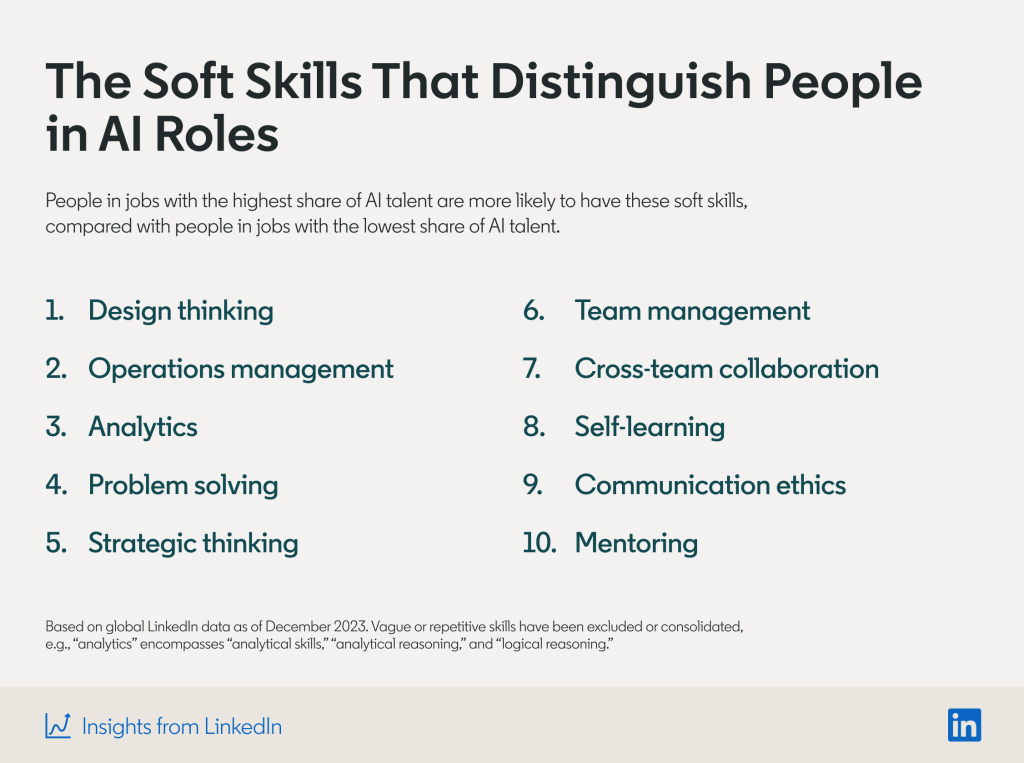

Make sure to include your soft skills too

As a talent pro, you may know the old saying: “Hard skills get you the interview but soft skills get you the job.”

And yet most professionals are much more likely to add hard skills to their profiles than soft skills. Some of that is about math: LinkedIn, for example, has a catalog of some 41,000 skills and the overwhelming majority of them are hard skills.

But the bigger challenge may be that most workers don’t know how to identify or assess their own soft skills.

Soft skills are the attributes and abilities that shape how you work, interact, and communicate with others and they are transferable across teams, organizations, and industries. They include talents like effective communication, collaboration, leadership, listening, and problem-solving.

Soft skills are typically more subjective and more difficult to measure than hard skills. (Even the name “soft skills” is more squishy than its “hard skills” counterpart, with some people referring to them as “human skills,” “power skills,” or “people skills” instead.) Don’t push them aside.